Q&A with Composer and Cousin, Nicolás Lell Benavides

Nick, thank you for taking the time to talk with us about your upcoming opera Dolores and its preview performance on August 13th at The Taube Atrium Theater!

Audiences, funders, partners are so excited. But there are still some people who are just hearing about Dolores for the first time. Some audiences will know very little about Dolores Huerta and some will really know their California civil and labor rights history.

So, to get us situated: Who is Dolores Huerta to you personally, and who is she to California and this country?

Nicolás: I really think that we've designed the opera in a way so that people don't need to know a lot about Dolores Huerta at the start. They can be dropped right into the story in the best way possible.

Dolores Huerta is one of the most important people you've probably never heard of in this state, (laughing), in terms of the effect she's had on our culture, on labor rights, on the direction of progress of the state of California. I mean, she does have a state holiday you know, she's vitally important to the state of California… but we also understand that history skews towards men. History skews away from women and people of color. We're working on that historically as a society, but we understand the truth of where we are societally right now and we welcome you right into the story, even if you have no knowledge of Dolores Huerta before walking into the theater.

We give you all the information you need to know in an epic 25m opening scene, which I have to say, is one of my favorite things I've ever written! In this opening scene, we get you up to speed on the labor rights movement, on the struggle, on the persistence and the energy that she brought to the table in 1968.

And to me? To me, Dolores is my cousin. She’s an incredibly bright, wonderful person that I would see at family gatherings. And this may sound like a crazy thing to say, but honestly: she's the same person to everybody she interacts with. People have this opinion of really important, famous people who do things like win presidential medals of freedom as being types of people who are lofty and unapproachable. But the person you see on tv - the very kind, determined, dedicated individual is the exact same person at home with family. She's wonderful.

She has had such a rich life and continues to do so much… What are you focusing on in this opera? Which events/what time period… and why those events and time period?

We decided to focus on 1968 because, although that was not at all the beginning of her career, nor even close to the end of her career as it's still continuing today in 2023, 1968 served as a microcosm of her career. All of our careers are cyclical in that there is a cause, there's an injustice, there's a struggle, there's organization, there's finding the tools and the people to meet the moment, pulling it together, and then facing unexpected setbacks. Repeat. For Dolores, the assassination of Bobby Kennedy in 1968 was probably the worst unexpected setback she's ever experienced. And for us, if she could push through that setback and provide leadership in a time like that…well, it creates a mythological sort of survey of the type of person she is for the rest of her career after that event.

We chose this moment to show how she handles the highest states of overcoming. Because when you learn about the rest of her life, up till today, it makes sense that she is the way that she is and that she's undeterred, completely unflappable.

And it’s a mythical moment in time. I mean, all the civil rights leaders, all the politicians involved: Bobby Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis, Richard Nixon, the Vietnam War just looming, right? What a time. And I think it's a reminder that we live in a historic time now too. There were different underpinnings then, but people overcame those moments as we will overcome the challenges of these current times.

I love your phrase mythological survey. That's a beautiful way to frame how an author captures the spirit of a real person, but a real person with a very big legacy.

I think it has to be mythological. I was thinking a lot about this idea when I wrote the music because I could have been more realistic—a sort of documentary style—which I always knew was the wrong move. The opera stage gives us mythology better than anything, right? So, I went for the myth of who Dolores was at that time, the symbol that she was at that time.

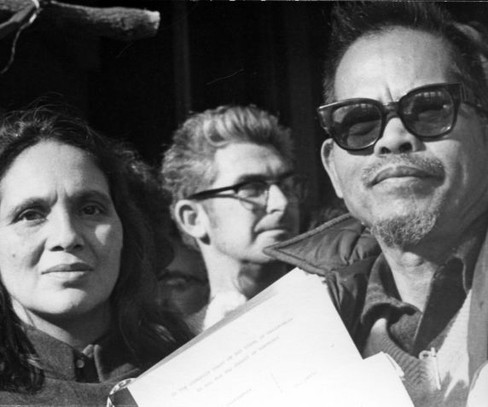

Photos (L-R): Dolores Huerta with Larry Itliong. Huerta with Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.

Did you find that by centering Dolores Huerta in the opera when perhaps history has more sidelined her than other important men… that it changed the way you constructed other historical characters like Cesar Chavez or Bobbie Kennedy or Larry Itliong?

In the opera, they now all feel mythological to me. Even Juan Romero, the busboy, now feels like a mythological character. Like in the Odyssey.

I didn't know that your character Juan Romero was a real person.

Oh yeah. There are photos of him holding Bobby Kennedy, and interviews with Juan Romero just from a few years ago. He talked about how terrible and guilty he felt about not being able to do anything, even though he literally couldn't do anything. He was a busboy with a rosary. Those photos capture everything about the essence of that time - it's why he gets a solo in the opera, even though he gets no other moments. For me, Juan Romero symbolizes all the hopes and dreams of the young people who have the naivete to not understand exactly how the world works, but the fortitude and the bravery to just go for it—to feel like they can affect change. I think he was 17 the moment that he was holding Bobby Kennedy in his arms. He must have grown to a full adult in the span of an evening, right? With the weight of the world on his shoulders. I mean, what's more mythological than that?

Tell us a little bit about your musical style, your influences. What's inspiring you, and how is that maybe showing up in your composition for Dolores?

Well, I'm a young father, so naturally I'm really obsessed with Steely Dan right now. (laughing) No no, but seriously, I feel like the older I've gotten, the more I’ve accepted that lots of people's fingerprints are going be on my music—that I'm just going to reach for the tools in front of me —very postmodern maybe, the tools that that serve a moment. In this piece, the opening is kind of minimalist where there's strong refrains and huge rushes and then these sort of zoom into different moments… and there's like a weird bossa nova at one point (laughing).

Bossa Nova!

I don't know why, except that it felt right! I trust my instincts and reach for what works. There's Latin dance music, there’s an electric guitar – a pulsing energy that happens whenever Dolores starts to really get things going. The saxophone is a kind of sinister voice Nixon…I feel like everything I've ever worked on, and this sounds hyperbolic, but it's true, has come to play in this opera so far with only the first hour done. Like every skillset I think I've ever developed. I even wrote a five-part counterpoint at one point, which I haven't done in years. But during a Dolores prayer scene, I set the Salva Regina, a Catholic Gregorian chant, and I kind of arranged the melody underneath pedal tones in a Britten-esque, five-part contrapuntal harmony fugue thing—I don't know how to describe in words what I'm doing! But it feels right, because the weight of the world is on Dolores’ shoulders in this particular moment in the opera, and there is a thicket of problems for her while she just keeps moving forward. I've really tapped everything from all of my musical experience—I have to for this opera. It's been exhausting, but so good.

So what does a preview performance on August 13th mean for you?

I mean, composers like to talk about how everything has to live in our imagination. But what a lot of composers will admit if you get a beer with them is that our imaginations are so woefully inadequate. Our imaginations can really only take us so far. We are in an art form that is at the mercy of other people's art forms. We are like the world's biggest symbiotic species artistically because we are completely voiceless and completely declawed and defanged and unable to fend for ourselves unless we have singers and actors and stage directors and lighting.

And I am not a composer who just writes symphonies by myself in my room and hopes that people find them when I die. I absolutely need the energy in the room. And so for me, sure, my imagination has got me pretty far. It's 1600 measures long (laughing) like 257 pages - It's the biggest thing I've ever written and it's only halfway done. So, I have to have some kind of imagination. But to be in the room is so different. Not to just verify that what I thought I heard is correct, but really to change things. Like, is the singer being overpowered by the trombone? Is that the tonal color I meant to establish? Do I need to come knocking on West Edge Opera’s door for more money to hire a Contra Bassoon? I don't know! We’re going to find out on August 13th!

Where are you in your process of composing?

Oh, the worst, the worst place possible! I'm making parts. Which, anybody who knows anything about composing knows that making parts is the sewer work of composing.

Say more! The sewer work?

So I made the score, which is what the conductor's going to use. Mary's going to be reading from the score. And I did my best to format it properly. But imagine every player in the orchestra: the violinist, the saxophones, the percussionists, they all need to look at just their part. And the computer doesn't make that automatically for you. It tries, but it does a terrible job. So, I have to go in measure by measure for every single player and look at everything that they're going to look at. Pretend I'm the percussionist for a day, pretend I'm the violinist for the day. Pretend that I am the cellist. Pretend like if I had this on my stand, would it serve me well? And if the answer is no, I have to fix it. I have to fix it so that they're not raising their hand in the middle of an important and expensive rehearsal asking questions like: ‘measure 438, there's a forte and a piano—what does that mean?’ (laughing) I have to catch as many mistakes as I can to save the sanity of everybody in the room.

My final question, and I’m not completely sure how to ask this but…it is scary to compose something inspired by a family member that you love? We all have people in our lives that we love and inspire us to a very large degree. But to make an opera inspired by them…while they’re still here on this planet to see it…is that daunting?

You know, the more I work on the opera, the more I get a clearer vision of not just who she is in the real world, but who Dolores is on stage. And really, how those two Dolores Huertas are a little bit different. They're spiritually the same. They're connected, but it’s almost like they’re in different multiverses of one another. And that clearer vision has allowed me to accept that the Dolores of the opera world. I’m not here to tell a story for the sake of benefiting her foundation or her political interest . I’m not a propogandist. I'm here to tell an American story with real American heroes fighting for real American justice…and that’s a mythic opera.

And she has been so generous, even when I saw her last month she said to me: I trust you. I think she knows what my motivations are and that is why she has been so forthcoming. And it's a risk, you know, she might be disappointed with certain parts of it.

She might not like it musically. She might disagree with a line that she says. But I think her legacy is the actual work that she's done. I don't think in the grand scheme of things she's actually concerned with how she looks in an opera because her work is in the field. It's giving interviews to fundraising for people in need. The opera is nice - it’s really nice! But the opera is not her legacy. The opera is a tribute to her legacy.

Comments